CHAPTER 1

Introduction to Blazor

In this book, you will learn about Blazor,

a modern framework for developing web applications using C#.

You’ll learn about all the features of Blazor,

from the most basic to the more advanced.

You will learn the fundamentals of Blazor syntax and project setup,

as well as exciting modern features

such as picking files and accessing them using C# in a web browser,

accessing API data using JSON, and using many of the other

latest features of Blazor.

In addition, I will demonstrate what you can achieve in Blazor

and provide a few tasks for you to practice yourself,

along with the solutions I created for them.

Before you start, you need to know and prepare a few things.

This is not an introductory book to C# or .NET Core development,

so you should already have good knowledge of C#

and be able to build applications with it.

It does not matter if you develop back-end applications,

Windows applications, or mobile applications;

as long as you use C#, you will find something familiar in Blazor.

If you haven’t already,

you’ll need to install Visual Studio 2022

and make sure that you have the .NET 7 SDK installed

on your computer.

What Is Blazor?

Blazor is a web UI framework

that allows you to use C# and .NET Core on the front end.

It allows you to develop your front-end logic

in a couple of different ways using the C# programming language,

which is something that you will explore later in this chapter.

Technical aspects aside, think of it this way:

in any standard web development project,

you would need to have two people,

one for the JavaScript and the other for the back end.

Sometimes you also need a designer to work with HTML elements and CSS

and do other design-related tasks.

The Blazor technology will not remove any dependency for a designer,

but it will surely remove the dependency on JavaScript.

(However, JavaScript can still be used with the Blazor technology.)

Blazor uses the Razor syntax (C# mixed with HTML),

which will be covered in Chapter 2,

so any familiarity with the Razor syntax will give you an edge when developing.

There are some differences, though, as you will see shortly.

Most important,

your C# code in Razor (the .cshtml file) will execute

only when the page is loaded,

but in Blazor (the .razor file)

the code will execute on the loaded page on various events,

such as onclick, onchange, and others.

Blazor uses WebSocket to communicate with the server

as well as work on the server side,

or it uses the WebAssembly technology,

which allows for C# to be built on the client side.

This is where the different types of Blazor technology come into play.

What Is WebAssembly?

WebAssembly is a technology

that allows you to compile languages such as C++ or C# in the browser,

thus allowing Blazor to exist.

It first appeared as a minimum viable product in early 2017,

and while the technology is still in its early years,

it is being co-developed by companies

such as Microsoft, Google, Apple, and others.

The technology has the support of most major browsers

(https://webassembly.org/roadmap/)-Edge, Chrome, Firefox,

Opera, and Maxthon (MX)—and the equivalent mobile versions.

With its growth, we can expect the support to be there for a long time.

In general, Blazor simply sends a source code file to the browser,

and WebAssembly compiles it into a binary file.

WebAssembly gives you

a safe, sandboxed environment, so it appears similarly as running JavaScript.

Nothing is accessible from outside the specific browser tab the user is using.

Blazor Types

The server-side type of Blazor will run all the logic on the server side,

mainly using WebSockets to accomplish tasks (Figure 1-1).

Although it does give you an ability to use C# to write the front end,

this may not be the most efficient option.

You will eliminate the need for API calls with this option,

as you will simply inject your libraries directly to the front-end part.

The client type of Blazor runs completely on the client side,

on the browser (Figure 1-2).

You will have your pages on the server, but other than that,

the client side handles everything. So, this is great for presentation websites

or websites that provide calculators and other such services.

If you need database interactions or if you already have APIs and class

libraries, this will not be your choice.

There are also other possible variations of these two types.

One of them is Blazor hosted;

this project is client-side Blazor (Blazor WebAssembly) interconnected

with the web API project.

The client Blazor and API program run separately,

but development-wise they will be able to share a common code library,

mostly for data models.

There is also a progressive web application (PWA) option,

which allows the Blazor client to run offline.

Finally, you can add API capabilities (controllers and such)

to a Blazor server project.

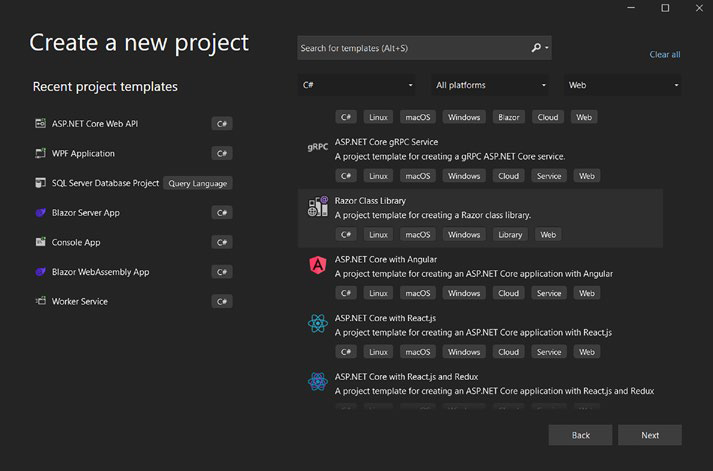

Along with these main projects,

you will also find a Razor Class Library project (Figure 1-3).

This allows you to create Blazor components

with all the Blazor features in a code library

and if needed publish that to NuGet.

Summary

There is no best type of Blazor;

as you have seen throughout this chapter,

every option has its own use case.

Everything depends on what your project needs right now

and, more important, what it will need in the future.

If you are not sure, simply go with the client-side version,

as it will be the most diverse option.

In the next chapter, we will dive deeper into Blazor

and explore the syntax and some other topics.

You will see that while the structure may be different,

for the most part, coding happens in the same way for all types of Blazor

CHAPTER 2

Razor Syntax and the Basics of Blazor

This chapter will get you started with Blazor.

As mentioned in the previous chapter,

all three types of Blazor have a lot in common.

Before we can go any further,

we will need to look at the syntax and see how it works.

Then we will get into the essentials of Blazor,

such as bindings and method execution;

all of these topics will be used later in the book.

In this chapter, you will learn about the following:

• Syntax

• Element and variable bindings

• Method executions

• General page events

Differences Between Razor and Blazor

Simplistically speaking,

the difference between Razor and Blazor is

that Razor will be executed once on page launch,

while the Blazor functionality will work all the time.

In other words,

the loops and logic statements will get re-evaluated in Blazor,

while with Razor it will happen only once.

Syntax

As mentioned previously,

if you know Razor syntax, you will know Blazor syntax.

However, if you do not know Razor syntax, this is the section for you.

The Blazor code goes into a markup file named .razor,

which contains HTML as well as C# code.

Comments

Even though we use HTML syntax in a Blazor file,

we do not use HTML comments.

Instead, we use Razor syntax

and get a beautiful and efficient commenting system,

with no comments left on a generated page. Listing 2-1

illustrates this.

Listing 2-1. Razor/Blazor Comment Syntax

@*

Below is a test p element

*@

<p>Test paragraph</p>

As shown in Listing 2-1,

you simply start a comment section with @* and then end with *@.

You can also use the standard HTML comments,

but using the Razor/Blazor syntax will be easier to see in the code.

The Razor/Blazor comment syntax characters get highlighted,

and the actual comment is displayed in green.

The comments will not be visible in published app

using browser developer tools.

Sections

Razor syntax is basically C# and HTML code in one file,

and while they do interact,

you need some higher contrast between the two languages.

That is where all the different sections come in; as you will see,

the sections are C# dominant,

and they are used to highlight the C# parts of the code.

In Listing 2-2,

a variable is being declared,

and then it is displayed directly in a paragraph using C# code.

So, for a single variable and the construction of classes,

you can simply use the @ sign and write everything on a single line.

If you want to write more than one line for a variable declaration,

you need to create a section using @{ ... }.

Listing 2-2. Basic Blazor Sections

@{

string teststring = “tst”;

}

<p>@teststring</p>

At this point,

this may look very simple, so let’s dive into a few more examples.

In Listing 2-3,

the testint variable is declared and set to the value 0,

followed by an if statement checking if the value of testint is not 0.

Since the statement criteria is not satisfied,

whatever is inside the if statement is not displayed.

If the testint variable is set to any other value than 0, say 1,

the HTML paragraph tag and value would be displayed.

The C# code in the @{ } section is highlighted,

and it requires no @ sign for each line.

The if statement part starts with the @ sign

and creates a section similar to the previous example.

This means the HTML code in the if statement section

is not highlighted in any way.

Listing 2-3. if Statement Syntax

@{

int testint = 0;

}

@if (testint != 0)

{

<p>Is not equal to zero</p>

}

In Listing 2-4,

a for loop has been created, looping five times.

Each loop creates a new paragraph tag containing the value

for the current iteration, i.

The for loop part is highlighted in a slight shade of gray,

while the @ signs are highlighted in yellow.

The HTML part inside the loop is not highlighted,

but the C# code is; that is how you can tell the difference

between HTML markup and C# code.

Listing 2-4. Syntax Coloring

@for (int i = 0; I < 5; i++)

{

<p>@i</p>

}

Finally, there’s the code section (see Listing 2-5)

where all the methods should be declared.

The binding variables should also be added to the code section,

which you will find later in this chapter (in the “Blazor Binds”section).

Listing 2-5. Code Section

<p>test</p>

@code {

int a;

double b = 2.5;

void testmethod() {

}

}Blazor Binds

Blazor allows you to bind an HTML input value to a variable and vice versa.

Therefore, for the most part, we can call all bindings two-way.

If you bind a text box (input type text) to a string variable,

the displayed value will be the value of that string.

Different elements will work differently,

and there are many use cases for this.

Binding to an Element

Binding to an element is simple.

Not all elements can be bound, but most can.

Elements where values can be bound to a variable are as follows:

• Input (except for file type)

• Textarea

• Select

The listed elements are the most common elements that can be bound,

but most others will work in some way.

In Listing 2-6,

two simple variables have been declared,

and initial have been values assigned.

Listing 2-7 shows how to bind them to different elements.

Listing 2-6. Variables

@code {

string teststring = "test value";

bool testbool = true;

}Listing 2-7. Bindings

<input type="checkbox" @bind="@testbool">

<input @bind="@teststring">

<textarea @bind="@teststring"></textarea>In Listing 2-7,

a Boolean value is bound to a check box, checked/unchecked,

and the same is true for a radio button.

The string value can be bound to any text value

such as input, textarea, and others.

When the input value changes,

the variable value changes, and when the variable value changes,

the value displayed in the input tag will change too.

The previous option can be considered a default option to do the binding;

however, there are additional parameters that you can use.

In Listing 2-8,

you can see a binding on a specific event, rather than the default one.

In this particular example,

you can see that the oninput event is specified,

and when it occurs, the input text will go into the displaytext string.

This is useful, because it gets displayed right away,

rather than the onchange event,

which requires for the input to lose focus for it to occur.

This example is most common,

and most other event/HTML tag combinations likely will not work.

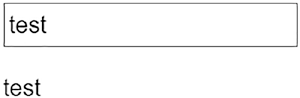

Listing 2-8. Bind on Specific Event

<p><input type="text" @bind:event="oninput"

@bind="displaytext" /></p>

<p>@displaytext</p>

@code {

string displaytext = "";

}In general, the value that you bind needs to be present in the event

arguments for the event specified.

Events

The code section is where the C# methods for the front end are added.

The code sections are meant to contain your code for the client side,

variables, and methods.

It is much like a <script> tag in a standard HTML page,

but there’s more to it, as shown in Listing 2-9.

Listing 2-9. Variable Display

<p>@testvar</p>

@code {

string testvar = "test variable";

}In Listing 2-9,

a variable is declared, and then it is added to a paragraph tag.

This is quite special, as shown in Listing 2-10.

Listing 2-10. Onclick Event

<p>@testvar</p>

<p><button @onclick="@testmethod">change</button></p>

@code {

string testvar = "test variable";

void testmethod() {

testvar = "test";

}

}In Listing 2-10,

the same variable as in Listing 2-9 is declared

and then displayed in the paragraph tag.

There’s also a C# method, which, in clientside Blazor, will run on the front end.

The method is called by declaring it in the onclick event attribute for the button tag,

but parentheses should not be used.

The method simply changes the value for the variable,

and in turn what is displayed in the paragraph tag is also changed.

So, that is a oneway binding, and in Listing 2-11, a two-way binding is shown.

Listing 2-11. Bind, Onclick, and Display

<p>@testvar</p>

<p><input @bind="@testvar"></p>

<p><button @onclick="@(() => testmethod())">change</button></p>

@code {

string testvar = "nothing to display";

void testmethod(){

testvar = "test value";

}

}In Listing 2-11,

an input tag is bound to the testvar variable,

so whenever the input tag value changes, the variable will also change,

and therefore the display in the paragraph tag also changes.

Do note that the input tag must lose focus for it to take effect.

So, that is how to call a method accepting no parameters.

While it is not recommended,

Listing 2-12 shows how to pass and accept parameters.

Your method could also be a Task method,

and you would be able to await it in that lambda expression.

Listing 2-12. Method with Parameters

<p>@testvar</p>

<p><input @bind="@testvar"></p>

<p><button @onclick="@( () => testmethod("test var"))">change

</button></p>

@code {

string testvar = "nothing to display";

void testmethod(string testparam){

testvar = testparam;

}

}In Listing 2-12,

the method accepts the testparam parameter.

So, use parentheses on the method call,

and pass the value to call the method,

rather than declaring it for the event almost like a variable.

Use a lambda expression, and then use the method normally.

This can be useful if different values are needed in the list output.

To use a Task method, a lambda expression should be used as well.

As shown in Listing 2-13,

it is quite easy to do,

but it is recommended to use the await keyword

and use a Task with an async method.

Listing 2-13. Asynchronous Task

<p>@testvar</p>

<p><input @bind="@testvar" /></p>

<p><button @onclick="@(async () => await testmethod())">change</button></p>

@code {

string testvar = "nothing to display";

async Task testmethod(){

testvar = "test value";

}

}Finally, you are not limited to one method;

there is also an option to execute several methods

in each event and/or simply set variables directly in the event.

In Listing 2-14,

you can see how a Boolean variable is set to true when the button is clicked,

without the use of an additional method.

In that area, you could also execute additional methods

or use if statements and other logic.

If you want to use await,

you will simply need to add the async keyword like you saw

in the previous example.

This option can make your code look cleaner in the code section,

but it should not be abused as it might make the HTML part a lot less readable.

Listing 2-14. Direct Use of Event

<p><button @onclick="@(() => { buttonclicked = true; })">Click button</button></p>

@code {

bool buttonclicked = false;

}

Event Arguments

Each event has its own argument;

for example, the input contains the input text.

In a way, this is how bindings work;

you just do not have to access the arguments directly.

But there are cases where you need to, so here is how to do it.

In Listing 2-15,

you can see the oninput event being used

and the argument from that assigned to the testvar string.

To retrieve an argument, you simply set a name in the setup for the event.

This variable in this case is an object (it can be converted to a string, but for numerics you

can use double, int, or something else).

Listing 2-15. Event Overrides

<p>@testvar</p>

<p><input @oninput="@((args) => { testvar = args.Value.ToString(); })" /></p>

@code {

string testvar = "";

}

It is important to note

that the arguments for the events in Blazor and in JavaScript

are not always the same.

Page and Component Lifecycle Events

Whenever the user loads a page (or a component),

some events are triggered.

These can be used

to invoke your procedures on various stages of a page/component cycle.

The first and likely most common event is OnInitializedAsync (Listing 2-16).

This event occurs before the page gets rendered.

If you have to pull data and display it without user input,

this is where such procedures should go.

Listing 2-16. Event Overrides

@page "/"

<h1>Index page</h1>

@code {

protected override Task OnInitializedAsync(){

return base.OnInitializedAsync();

}

}After the page gets rendered,

the OnAfterRenderAsync event occurs (Listing 2-17).

This can be used for procedures that require UI elements to

be fully loaded.

Listing 2-17. Event Overrides

protected override Task OnAfterRenderAsync(bool firstRender){

return base.OnAfterRenderAsync(firstRender);

}This event will also recur

if there are any updates to the page

or if StateHasChanged() has been invoked (covered later in the book).

Therefore, if you want to use it only on the initial render,

you can check if the Boolean value is true.

Finally, OnParametersSetAsync (Listing 2-18)

will occur when a new parameter is set. You will learn more about parameters later in the book;

this event mostly applies to components.

Listing 2-18. Event Overrides

protected override Task OnParametersSetAsync(){

return base.OnParametersSetAsync();

}

Summary

You now know some basics of Blazor,

as well as the most important parts of it:

bindings and method executions.

In the next chapters,

we will dive deeper into Blazor

and explore the differences between the different types.

With that, we will not forget the basics,

and you will see something from this chapter occurring

in almost every example of code in this book.

CHAPTER 3

Blazor Components and Navigation

This chapter will introduce the specifics of Blazor pages and components.

You will learn

how page files are created and

how navigation is set up.

Then you will learn all

that you need to know about components and their features,

such as parameters, custom events, and more.

Pages and Navigation

In general,

a page in Blazor is a .razor file that contains your code,

and it has a route to it specified in the code.

It can also read parameters,

and that same file can act as a component,

which you will learn more about later in this chapter.

Page files should be added to the Pages folder in your Blazor project

or in subfolders of that folder.

The location of the file does not matter;

the page route will depend on what you specify in @page.

Listing 3-1 demonstrates this.

In the following example, you can see two pages.

The index page always has an empty route by default, as shown in Listing 3-1.

The second page is called page 1, and the route specified for it is page1.

The structure of this statement is very important.

First you use the @page directive;

then you follow that by a route enclosed in quotation marks and starting with

the / character, as shown in Listing 3-2.

Listing 3-1. Contents of Page1.razor

@page "/page1"

<p>page 1</p>

Listing 3-2. Contents of Index.razor

@page "/"

<p><a href="/page1">navigate to page 1</a></p>Pages can also have parameters passed on navigation.

This can be achieved in two ways;

you can do it using Blazor-specific techniques,

which is a more modern, easier, but also somewhat limited option.

Or, you can simply parse and read the URL of the page, as shown in Listing 3-3.

Listing 3-3. Contents of Page1.razor with Parameter

@page "/page1/{ExampleParam}"

<p>page 1</p>

@code {

[Parameter]

Public string ExampleParam { get; set; }

}For the first option,

you will need to declare a variable for Parameter in the page file.

The structure of this is important.

You need to use [Parameter],

it has to be public, and it has to have { get; set; }.

Finally, this will work only for a string,

although in components it is possible to use other types too.

In addition, it has to be declared in the route string,

as shown in Listing 3-4.

Listing 3-4. Contents of Index.razor

@page "/"

<p><a href="/page1/paramvalue">navigate to page 1</a></p>You can have several parameters (Listing 3-5);

however, the route that

you set has to be fully complete to navigate to. In this case, any link to that

page must contain those two parameters in that same exact order.

Listing 3-5. Contents of Page1.razor

@page "/page1/{ExampleParam1}/{ ExampleParam2}"

<p>page 1</p>

@code {

[Parameter]

public string ExampleParam1 { get; set; }

public string ExampleParam2 { get; set; }

}If you want to have more flexibility,

you can set several routes (Listing 3-6).

This example allows navigating with both parameters,

with one parameter, or without parameters at all.

In such cases,

the parameter properties set in the page

would simply have their default values.

Listing 3-6. Contents of Page1.razor

@page "/page1/{ExampleParam1}/{ ExampleParam2}"

@page "/page1/{ExampleParam1}"

@page "/page1"Parameters can be accessed on the life-cycle events starting from the first one,

OnInitializedAsync (refer to Chapter 2).

Components

Components are the same files as pages,

with pretty much the same features.

But instead of being navigated to, they are declared inside pages.

See Listings 3-7 and 3-8.

Listing 3-7. Contents of ExampleComponent.razor

<p>Example Component</p>

Listing 3-8. Contents of Page1.razor

@page "/"

<p>Index Page</p>

<ExampleComponent></ExampleComponent>In this basic example,

we have a new Razor file (ExampleComponent.razor) created in the Pages folder.

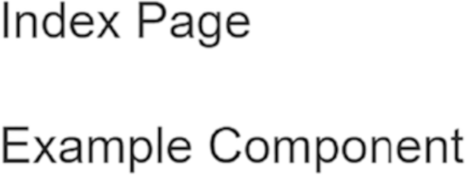

As you can see in Figure 3-1,

the component simply blends into the parent page (or component) code.

And it is declared like any other HTML element.

If the component were placed in a different folder,

you might have to declare the whole path.

For example, if the component were in the Components folder,

which is in the Pages folder, the statement would then be

<Pages.Components.ExampleComponent>.

Parameters

In Listing 3-9,

we have two parameters: one string and one DateTime. In

components, a parameter can be whatever type you want such as your own

custom object and another type.

Listing 3-9. Contents of ExampleComponent.razor

<p>Example Component</p>

<p>@param_string: @param_date.ToString()</p>

@code {

[Parameter]

public string param_string { get; set; }

[Parameter]

public DateTime param_date { get; set; }

}The parameters are set directly in the component declaration (Listing 3-10),

similar to how you would set parameters for HTML elements.

Listing 3-10. Contents of Index.razor

@page "/"

<p><input @bind="@forstringparam" @bind:event="oninput" /></p>

<ExampleComponent param_string="@forstringparam" param_date= "@DateTime.UtcNow"></ExampleComponent>

@code {

string forstringparam { get; set; }

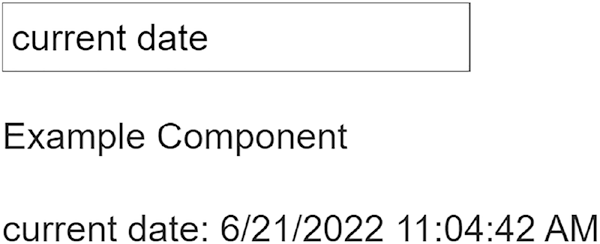

}Figure 3-2 shows the result;

when the string parameter binds,

it will bind on every change of the input box

without having to lose focus on the input.

Custom Events in Components

Components can take data from a parent,

but they can also return data to the parent (component or page).

This can be done as a two-way binding.

Also, it can have your custom events, possibly with event arguments.

In Listing 3-11,

we have a basic event (with no arguments).

An event is essentially a parameter of a specific type that is EventCallback.

You also need to make sure to have Parameter, public, and {get; set;}

in that statement for it to work.

To invoke the event, you simply use the InvokeAsync method.

Listing 3-11. Contents of ExampleComponent.razor

<button @onclick="@UseExampleEvent">Try it!</button>

@code {

[Parameter]

public EventCallback ExampleEvent {get; set;}

async Task UseExampleEvent(){

await ExampleEvent.InvokeAsync();

}

}Your custom event (Listing 3-12) is used the same as the regular HTML

such as onclick and others (refer to Chapter 2).

Listing 3-12. Contents of Index.razor

@page "/"

<p><ExampleComponent ExampleEvent="@HandleExampleEvent">

</ExampleComponent></p>

<p>@result</p>

@code {

string result;

async Task HandleExampleEvent(){

result = "Event has been used";

}

}If you want to provide event arguments, you just need to declare

the argument type in the EventCallback setup. In this example, it is a

string, but it can be anything you want. Then, the data is provided in the

parameters for the InvokeAsync method (Listing 3-13).

Listing 3-13. Contents of ExampleComponent.razor

<button @onclick="@UseExampleEvent">Try it!</button>

@code {

[Parameter]

public EventCallback<string> ExampleEvent {get; set;}

async Task UseExampleEvent(){

await ExampleEvent.InvokeAsync("Event has been used");

}

}

Once again, to handle the invoked event, you do it the same way as you

would for regular HTML element events (Listing 3-14).

Listing 3-14. Contents of Index.razor

@page "/"

<p><ExampleComponent ExampleEvent="@HandleExampleEvent">

</ExampleComponent></p>

<p>@result</p>

@code {

string result;

async Task HandleExampleEvent(string argument){

result = argument;

}

}

And just like in generic events, you can forgo the method setup

(Listing 3-15).

Listing 3-15. Contents of Index.razor

@page "/"

<p><ExampleComponent ExampleEvent="@((argument) => { result = argument;})"></ExampleComponent></p>

<p>@result</p>

@code {

string result;

}

Custom Binds in Components

Just like you can have custom events,

you can also have custom binds in your events

and then use them exactly like you would in regular HTML.

To establish a binding,

you will need to use a parameter property and a custom event.

The EventCallback type should be the same as a parameter;

it should also have the same name except the event parameter needs to

end with the word Changed.

The binding will occur when InvokeAsync (Listing 3-16) is executed

and the new value is passed.

Listing 3-16. Contents of ExampleComponent.razor

<button @onclick="@(() => { ExampleValueChanged.

InvokeAsync("test value"); })">Add value</button>

@code {

[Parameter]

public EventCallback<string> ExampleValueChanged {get; set;}

[Parameter]

public string ExampleValue {get; set;}

}

To use it, you need to specify the parameter with the bind property

(Listing 3-17).

Listing 3-17. Contents of Index.razor

@page "/"

<p><ExampleComponent @bind-ExampleValue="@result"></ExampleComponent></p>

<p>@result</p>

@code {

string result;

}You can also have several events

for the same bind property (Listing 3-18) (Parameter).

To do this,

in the component you will have to add another event (no rules for the name)

and then invoke it where you need it.

Listing 3-18. Contents of ExampleComponent.razor

<button @onclick="@(() => { SecondEvent.InvokeAsync("test value"); })">Add value</button>

@code {

[Parameter]

public EventCallback<string> SecondEvent {get; set;}

[Parameter]

public EventCallback<string> ExampleValueChanged{get; set;}

[Parameter]

public string ExampleValue {get; set;}

}Then in your page (or parent component), you will need to specify the

event on which to bind (Listing 3-19). This is the same as you would do

with regular HTML, for example, oninput for the input tag.

Listing 3-19. Contents of Index.razor

@page "/"

<p><ExampleComponent @bind-ExampleValue="@result" @bind-Example Value:event="SecondEvent" ></ExampleComponent></p>

<p>@result</p>

@code {

string result;

}

Layouts

The pages are loaded inside a layout in Blazor;

this can be modified in the MainLayout.razor file,

which can be found in the Shared folder.

The most important part is @body (Listing 3-20). This is where your

pages will be generated. By default, you will get an example layout,

but before building a real-world application, you should get rid of it all

and make your custom base layout.

Listing 3-20. Contents of MainLayout.razor (Default Template)

<div class="page">

<div class="sidebar">

<NavMenu />

</div>

<main>

<div class="top-row px-4">

<a href="https://docs.microsoft.com/aspnet/" target="_blank">About</a>

</div>

<article class="content px-4">

@Body

</article>

</main>

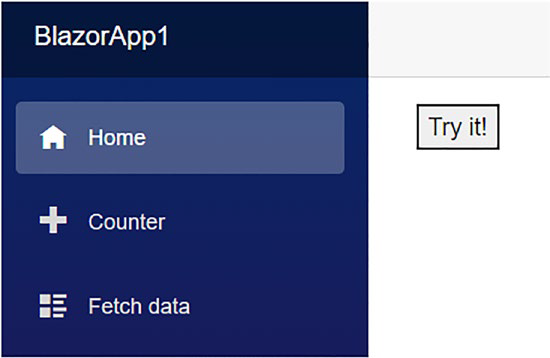

</div>In the default setup, the pages will go into the article tag of HTML.

The end result is that the page is displayed to the right of the

navigation menu (Figure 3-3).

Listing 3-21. Contents of MainLayout.razor

<div>

@Body

</div>If you remove all the default code and simply place @body in a div, the

end result will look like Figure 3-4.

Summary

In this chapter, you saw lots of features for pages and components,

as well as ways to arrange your code in a readable and useful way.

You may also have noticed

that some of the features may not seem very intuitive for regular use.

However, a lot of these will be useful when building Blazor libraries,

which are sets of Blazor code for others to use.

That and a lot more will be covered in the upcoming chapters.

CHAPTER 4

Specifics of Different Types of Blazor

Different types of Blazor, also known as hosting models,

are in general similar, but there are a few differences

that must be remembered to avoid malfunctions in your projects.

In some cases,

certain things simply will not work on one of the types,

or the behavior of a feature might change depending on the Blazor type.

In this chapter, you’ll learn the following:

• Overview of default Visual Studio templates

• Handling API access in Blazor

Default Template Overview

You will find some interesting differences

between the client-side (WebAssembly) and server-side templates.

You will also learn how to customize things when needed.

Blazor Server-Side Template

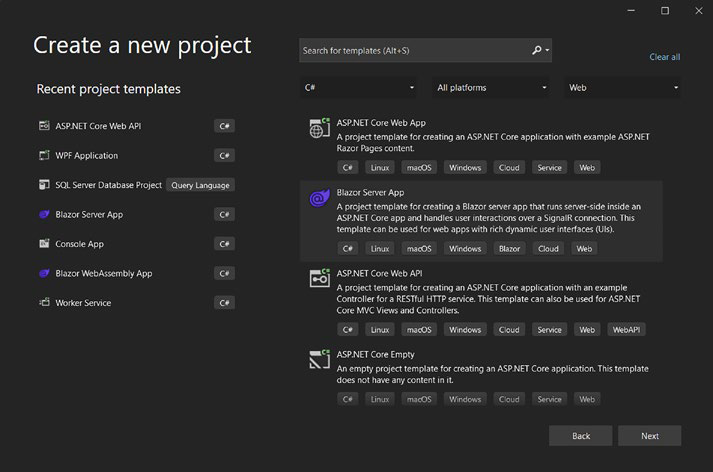

For the Blazor server-side version,

you have two template options at the moment.

One is called “Blazor server app,”

which includes some example code

that you will have to remove once you start your project;

the other is “Blazor server app empty,”

which is the one you should choose for this chapter (see Figure 4-1).

The Blazor server version essentially runs all its logic on your servers

and sends rendered pages to be displayed in a browser.

The input and output interactions are done via an active WebSocket.

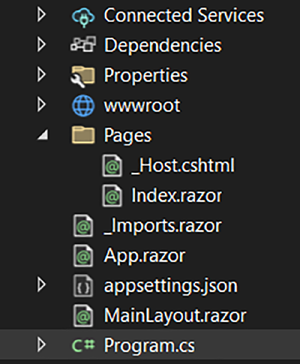

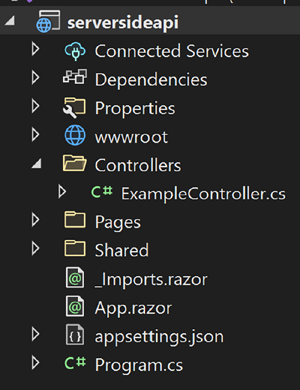

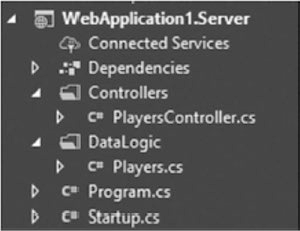

Figure 4-1. File contents of the “Blazor server app empty” template

In the Blazor server version,

you get several default files (shown in Figure 4-1),

which, for the most part, should not be modified.

Listing 4-1

shows the default contents of the Program.cs file.

Listing 4-1. Program.cs Default Contents

builder.Services.AddRazorPages();

builder.Services.AddServerSideBlazor();

In Program.cs, the two Blazor-related services shown in Listing 4-2

must be added; if these statements are removed, it will not work.

Listing 4-2. Program.cs Default Contents

app.MapBlazorHub();

app.MapFallbackToPage("/_Host");

After that,

the Blazor navigation must be mapped;

otherwise, your application will not work.

However, the fallback page can be modified

if you want to use another file name for _Host.cshtml.

But notice that the fallback page is a Razor (.cshtml) file, not a Blazor file (.razor).

Navigation in general is handled by default in App.razor, which should not

be modified except for the “not found” display.

MainLayout.razor (Listing 4-3) contains a declaration of where all

the pages will be rendered. The @body can be wrapped in a div or other

container instead.

Listing 4-3. Default Contents of MainLayout.razor

@inherits LayoutComponentBase

<main> @Body </main>

Finally, the _Host.cshtml file is where your Blazor project is rendered.

This is where you can declare your JavaScript files and your CSS styles.

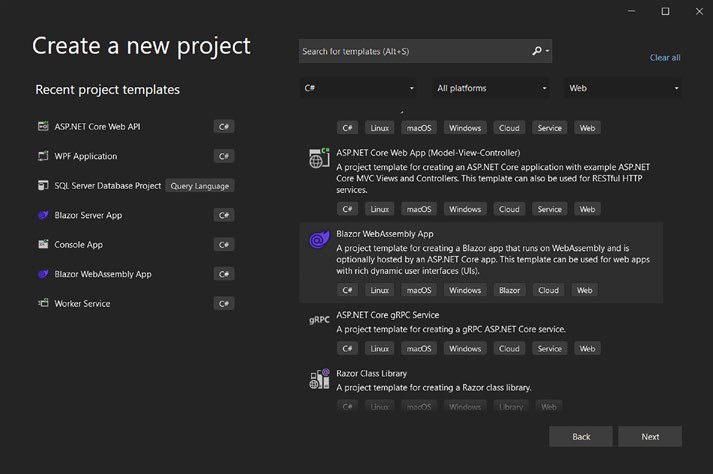

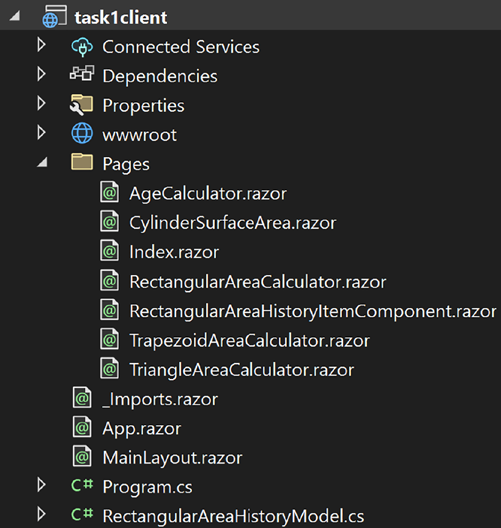

Blazor Client-Side (WebAssembly) Template

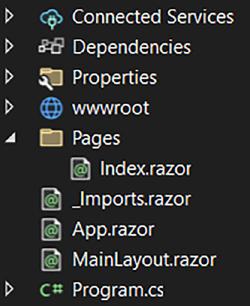

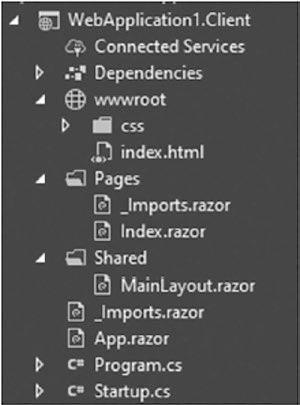

The two main differences between the client- and server-side hosting models

are the contents of Program.cs and the lack of a _Host.cshtml file

in the client-side Blazor version (Figure 4-2).

Figure 4-2. File contents of the “Blazor WebAssembly app empty”

template

Now, let’s take a look at the default code for Program.cs (Listing 4-4).

Listing 4-4. Default Code for Program.cs in the “Blazor

webassembly app Empty” Template

var builder = WebAssemblyHostBuilder.CreateDefault(args);

builder.RootComponents.Add<App>("#app");

builder.RootComponents.Add<HeadOutlet>("head::after");

builder.Services.AddScoped(sp => new HttpClient { BaseAddress =new Uri(builder.HostEnvironment.BaseAddress) });

await builder.Build().RunAsync();

The Program.cs file

first declares into what HTML tag everything will be rendered

and sets up the head.

You may notice that

this is basically the equivalent of what the _Host.cshtml file handles

in the Blazor server.

None of this should be modified,

as it may cause issues or cause the program to stop working.

What you can modify is your base address

if you are using HttpClient injections to connect to your API.

To declare your JavaScript and CSS files in the client-side Blazor version,

you will need to go to index.html (found in the wwwroot folder)

and do it there.

Injection

Dependency injection is mainly important for the server-side Blazor projects.

When injected, methods from that class can be accessed in any page or component.

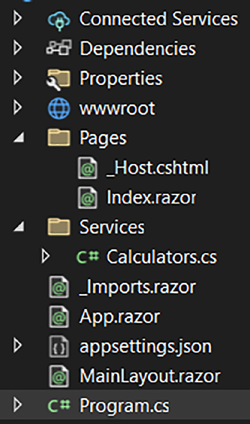

To understand this better,

Figure 4-3 shows an example of a very basic Blazor server application

(Listing 4-3).

Figure 4-3. File contents for the example project

In Listing 4-5,

we have one service class (Calculators)

that will be injected in Index.razor.

Listing 4-5. Index.razor

public class Calculators {

public async Task<double> Calculate(double a, double b){

return a + b;

}

}

The class itself contains only one method,

which adds two double values.

To inject a class, you need to use the @inject directive (Listing 4-6).

Listing 4-6. . Use of Inject in a Blazor Page

@page "/"

@inject Services.Calculators calculators

<p><button @onclick="(async() => { result = await calculators.

Calculate(5,5); })">Calculate</button></p>

<p>@result</p>

@code {

double result;

}However,

if you ran this right now and executed the method,

it would throw a major exception.

builder.Services.AddSingleton< Services.Calculators>();

To make this work, you need to declare this service in Program.cs.

Static Values

Static values must be used with caution in server-side projects.

Although they can be beneficial to hold global variable data,

it is important to remember

that these values will be used between sessions.

To demonstrate this problem, Listing 4-7 is a basic example.

Listing 4-7. StaticValues.cs Class in Blazor Server Project

public class StaticValues {

public static string StaticValue;

} Server side Blazor project contains one class with one static

string called StaticValue.

<p><input @bind-value="StaticValues.StaticValue" @bind-value:

event="oninput" /></p>

<p>@StaticValues.StaticValue</p>In Index.razor (Listing 4-7),

we have an input that binds straight to the static variable,

and the value is displayed (Figure 4-4).

Figure 4-4. Result of the example page

If the word test is inserted,

the result in the browser is as shown in Figure 4-4.

However, if you open another browser and paste the URL

for the running application,

you will see the same thing without having to insert anything into the input.

Calling APIs

The client-side Blazor project will likely require

accessing one or more APIs at some point

as the logic of it runs directly on the browser.

For this you can use HttpClient in a more traditional manner,

or if you use JSON, you can access that directly.

Listing 4-8 shows how to do it.

Listing 4-8. API Controller Example

public class ExampleController : Controller {

[Route("testget")]

public string TestGET() {

return "test result";

}

[Route("testpost")]

public string TestPOST([FromBody]DataToSend data){

return data.val1 + data.val2;

}

public class DataToSend {

public string val1 { get; set; }

public bool val2 { get; set; }

}

}

For the example controller, we have two basic routes:

one for the GET and one for the POST Listing 4-9.

You may also notice the data model class;

an exact match will have to be provided in the Blazor project as well.

Alternatively, if you have more of these model classes,

you may use a class library to store them.

Listing 4-9. HttpClient in the Blazor Page

@page "/"

@inject HttpClient http

<p><button @onclick="@RequestData" >Request data</button></p>

<p>Result: @result</p>

<p><button @onclick="@SendData" >Send data</button></p>

@code {

string result;

DataToSend datatosend = new DataToSend();

async Task RequestData(){

result = await http.GetFromJsonAsync<string>

("testget");

}

async Task SendData() {

datatosend.val2 = true;

result = await (await http.

PostAsJsonAsync<DataToSend>("/testget",datatosend)).

Content.ReadFromJsonAsync<string>();

}

class DataToSend {

public string val1 { get; set; }

public bool val2 { get; set; }

}

}

To access the JSON-based API,

you use either one of two methods: PostAsJsonAsync or GetFromJsonAsync.

For PostAsJsonAsync,

you will need to supply the class object that you are sending,

and the API must have a class in the same structure to be able to receive the data.

The response of that is an HTTP response,

which contains content and a few other things.

To read JSON content,

you will need to use ReadFromJsonAsync,

which gives you the same result as FetFromJsonAsync.

Adding the API Controller

The server-side Blazor project runs in a similar way to the .NET web API,

which means that you can integrate this capability into your Blazor project.

This will require adding a Controllers folder (and controller classes)

and a few things in Program.cs.

A good quick way to do it is to simply create an empty API project

and copy things that apply to API handling from there.

As you can see in Figure 4-5,

a Controllers folder has been added and, inside it,

a new controller file Listing 4-10.

Figure 4-5. Example project files

Listing 4-10. Method Execution from Program.cs

app.MapControllers();

For this to work, you need to add MapControllers

in the Program.cs file.

public class ExampleController : Controller {

[Route("/testroute")]

public async Task<string> TestRoute() {

return "test";

}

}

The controller itself will look and work the same as it would

in a regular .NET API project.

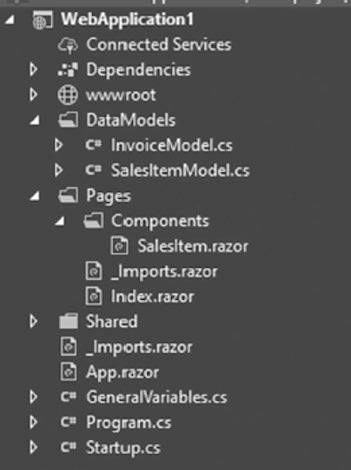

Blazor Hosted

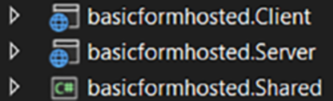

When creating a new Blazor project in Visual Studio,

you get a few options, and one of them is Blazor hosted.

This type simply adds an API project to a sort of shared assembly

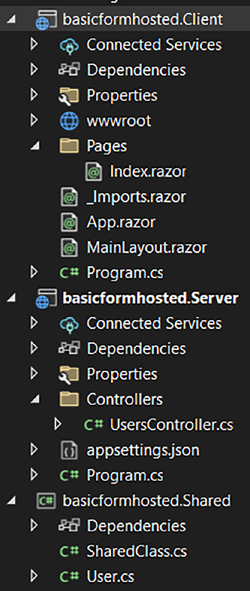

with your Blazor client project, as shown in Figure 4-6.

Figure 4-6. Projects contained in a Blazor hosted assembly

The Client one is your Blazor client project,

the Server one is your API project to which you can add controllers,

and finally Shared is a class library

that can host shared logic and/or data models.

You will later see a basic example done

with this and other types of Blazor.

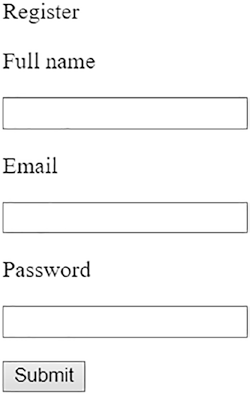

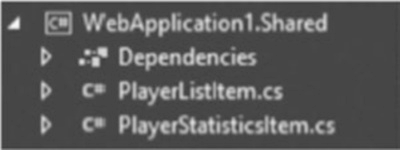

Basic Form Example for Two Types

of Blazor

This will be a basic example of a user registration form (Figure 4-7)

in the three Blazor types: server, client, and with hosted arrangements.

Figure 4-7. Basic form example view

You will see the differences between

the types and read explanations on why one is better or worse than the other.

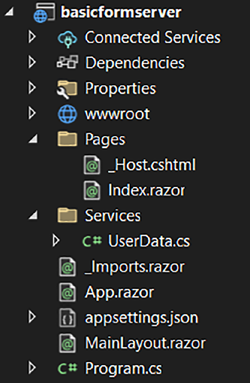

We’ll now look at the Blazor server version

with a simple one-project arrangement (Figure 4-8).

Figure 4-8. Blazor server project files

The form itself will go into the default Index.razor file, and the logic

will go in UserData.cs (Listing 4-11).

Listing 4-11. UserData class contents

public class UserData {

public async Task<bool> InsertNewUser(User newuser){

//insert into DB

return true;

}

public class User {

public string FullName { get; set; }

public string Email { get; set; }

public string Password { get; set; }

}

}

The service class simply contains the method, which when executed

would insert the data into the database. There is also a data model class for

the form data.

The interface part (Listing 4-12) uses the data model and binds the

inputs. Then on the click of the button, it executes the method to insert

data into the database. The UI itself will be the same as in the other

Blazor types.

Listing 4-12. UserData.cs

@page "/"

@inject Services.UserData userdata

<p>Register</p>

<p>Full name</p>

<p><input @bind="NewUser.FullName" /></p>

<p>Email</p>

<p><input @bind="NewUser.Email" /></p>

<p>Password</p>

<p><input @bind="NewUser.Password" /></p>

<p><button @onclick="@Submit" >Submit</button></p>

@code {

Services.UserData.User NewUser = new Services.

UserData.User();

async Task Submit(){

bool result = await userdata.InsertNewUser(NewUser);

}

}For the client-side part, you will also need an API project,

which contains one controller (Listing 4-13) with a class model for data.

Listing 4-13. UsersController.cs

public class UsersController : Controller {

[Route("adduser")]

public async Task<bool> AddUser([FromBody]User user){

// insert into DB

}

public class User {

public string FullName { get; set; }

public string Email { get; set; }

public string Password { get; set; }

}

}

Listing 4-14. Index.razor

@page "/"

@inject HttpClient http

<p>Register</p>

<p>Full name</p>

<p><input @bind="NewUser.FullName" /></p>

<p>Email</p>

<p><input @bind="NewUser.Email" /></p>

<p>Password</p>

<p><input @bind="NewUser.Password" /></p>

<p><button @onclick="@Submit">Submit</button></p>

@code {

User NewUser = new User();

async Task Submit() {

bool result = await (await http.

PostAsJsonAsync<User>("/adduser",NewUser)).Content.

ReadFromJsonAsync<bool>();

}

public class User {

public string FullName { get; set; }

public string Email { get; set; }

public string Password { get; set; }

}

}Instead of injecting and executing a method

like you would in the server-side version,

here you need to make an API call (Listing 4-14).

You will also need to set up the base address for HttpClient in Program.cs.

The Blazor hosted option is basically the same as on the client side.

We have a client-side Blazor and .NET API,

but in this case we also have a class library project (Figure 4-9).

Figure 4-9. Projects and project files

The difference in the controller is only that the data model comes from

a class library (Listing 4-15).

Listing 4-15. UsersController.cs

public class UsersController : Controller {

[Route("adduser")]

public async Task AddUser([FromBody] Shared.User user){

// insert into DB

}

}However, you can achieve a similar result

without having this hosted arrangement.

You can simply have a class library

that you use on both projects: client-side Blazor and .NET API.

The Blazor server part (Listing 4-16) is pretty much the same as

in client Blazor, except that the data model class is in a library.

The difference from the server-side version is

that we make an API call instead of executing a method directly.

Listing 4-16. Index.razor

@page "/"

@inject HttpClient http

<p>Register</p>

<p>Full name</p>

<p><input @bind="NewUser.FullName" /></p>

<p>Email</p>

<p><input @bind="NewUser.Email" /></p>

<p>Password</p>

<p><input @bind="NewUser.Password" /></p>

<p><button @onclick="@Submit">Submit</button></p>

@code {

Shared.User NewUser = new Shared.User();

async Task Submit() {

bool result = await (await http.PostAsJsonAsync<Shared.

User>("/adduser",NewUser)).Content.ReadFromJsonAsync<bool>();

}

}

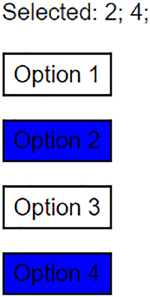

Multiple Select Example

This example shows how a multiple select can be made

using only basic buttons and C# code in Blazor.

The system is quite simple; we have four select options,

and whichever option is selected is highlighted in blue with

the number displayed on top (Figure 4-10).

Figure 4-10. Custom-made multiselect

For the values (Listing 4-17),

we have a basic dictionary, which contains the number of the selection,

and a Boolean value, which determines if it is selected or not.

In addition, we also have a method

that simply outputs a string for the background color statement in CSS.

For a more complicated styling change, you could use CSS classes instead.

Listing 4-17. Code Part of the Blazor File

@code {

Dictionary<int, bool> Selections = new Dictionary<int, bool>(){

{ 1, true},{ 2, false},{ 3, false},{ 4, false}};

string GenerateColorForSelection(bool is_selected){

if (is_selected) {

return "background-color:blue;";

}else {

return "background-color:white;";

}

}

}In the HTML part (see Listing 4-18),

we have four buttons representing four selections.

When a button is clicked, the Boolean value for

that specific selection changes.

Then the method to generate the background color is used

to set the color according to the selection status.

Then, the foreach loop goes through the dictionary

and displays the values that are selected.

Listing 4-18. UI Part of the Blazor File

<p>Selected:

@foreach (var item in Selections.Where(opt =>opt.Value == true)){

@(item.Key + "; ")

}

</p>

<p>

<button style="@GenerateColorForSelection(Selections[1])"

@onclick="@(() => { Selections[1] = Selections[1] == false ?

true : false; })">Option 1</button>

</p>

<p><button style="@GenerateColorForSelection(Selections[2])"

@onclick="@(() => { Selections[2] = Selections[2] == false ?

true : false; })">Option 2</button>

</p>

<p><button style="@GenerateColorForSelection(Selections[3])"

@onclick="@(() => { Selections[3] = Selections[3] == false ?

true : false; })">Option 3</button>

</p>

<p><button style="@GenerateColorForSelection(Selections[4])"

@onclick="@(() => { Selections[4] = Selections[4] == false ?

true : false; })">Option 4</button>

</p>

You can reuse this, but it must be in a component,

and you must use parameters with custom events (see Chapter 3).

This will also work on any of the Blazor types.

Summary

In this chapter you saw useful features for different Blazor types

and the differences between them.

But in the end,

the choice of Blazor type will always depend on your specific use case.

In the following chapter,

you will learn about several useful features

that can be applied to all Blazor types:

accessing JavaScript, using local storage, and more.

CHAPTER 5

General Blazor

In this chapter, you will find all the important features of Blazor that were

not covered in previous chapters as well as some use case examples to go

with them. Specifically, you’ll learn about the following:

• JavaScript interactions

• Local storage with Blazor

• Handling files

• Background tasks and examples

Interact with JavaScript

Although Blazor runs fully on C#, you will sometimes find cases where

you will be required to interact with JavaScript, such as when executing

JavaScript functions from C# or executing C# methods from JavaScript. Or

you might want to use third-party JavaScript libraries and access browser

features that are not available directly via Blazor.

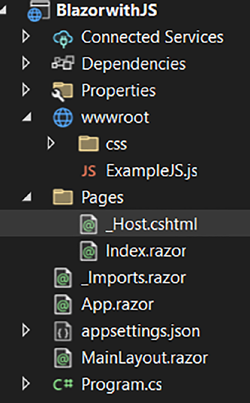

The project we’ll use to demonstrate this is a server-side project;

it simply contains the original Index.razor file and the newly added

ExampleJS.js file (as shown in Figure 5-1).

Figure 5-1. File contents of the example project

For now the JavaScript simply contains one function (Listing 5-1),

which will take a string value from C# and set it in JavaScript. Later we’ll

add more code to see how JavaScript can execute C# methods.

Listing 5-1. JavaScript Code

var JSvalue;

function SetValue(newvalue) {

Jsvalue = newvalue;

}

To execute the JavaScript function from C# (Listing 5-2), you will need

to add the IJSRuntime injection. Then use InvokeVoidAsync and set the

name of the function followed by any arguments the function takes. If the

function returns a value, you will need to use the InvokeAsync method and

declare the type of the returned value.

Listing 5-2. Blazor Code

@page "/"

@inject IJSRuntime js

<p><button @onclick="SetValueInJS" >Set value in JS

</button></p>

@code {

async Task SetValueInJS()

{

await js.InvokeVoidAsync("SetValue", "testvalue");

}

}

For the second part, we add two more functions (Listing 5-3): one

that will be executed on the click of a button and then execute the C#

method and another that sets the reference for the page (or it could

be a component). The C# method is executed by using the function

InvokeMethodAsync, which takes the name of the method followed by any

parameters it takes.

Listing 5-3. JavaScript Code

var JSvalue;

var pageref;

function SetValue(newvalue) {

JSvalue = newvalue;

}

function RetrieveValue() {

pageref.invokeMethodAsync('RetrieveJSValue', JSvalue);

}

function SetPageReference(pagereference) {

pageref = pagereference;

}

The UI part (Listing 5-4) has been expanded further too. It now

contains the page reference variable (DotNetObjectReference). For this to

work, you will need to create the page reference in the setup (before using

it); in this case, it is done on the OnInitializedAsync method, and the

function is JavaScript, which is used to set the reference there.

Listing 5-4. Blazor Code

@page "/"

@inject IJSRuntime js

<p><button @onclick="SetValueInJS" >Set value in JS

</button></p>

<p><button onclick="RetrieveValue();">Retrieve value from JS

</button></p>

<p>@jsvalue</p>

@code {

string jsvalue;

private DotNetObjectReference<Index> PageRef;

protected override async Task OnInitializedAsync()

{

PageRef = DotNetObjectReference.Create(this);

await js.InvokeAsync<string>("SetPageReference",

PageRef);

}

async Task SetValueInJS()

{

await js.InvokeVoidAsync("SetValue", "testvalue");

}

[JSInvokableAttribute("RetrieveJSValue")]

public async Task RetrieveJSValue(string newvalue)

{

jsvalue = newvalue;

StateHasChanged();

}

}

The method that is executed from JavaScript must be public and have

the JSInvokableAttribute attribute set. The parameter for that is used

in the JavaScript part to find and execute that method. In this case, the

method takes a value and sets it to a variable on the page. This requires

StateHasChanged to be executed; otherwise, the UI will not be updated.

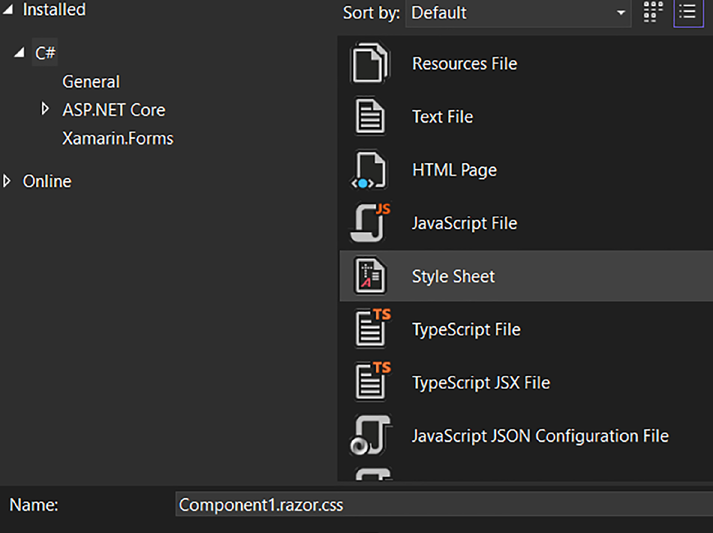

Code-Behind Files

Code-behind files can store CSS data and C# logic and are accessible only

to that specific file (page or component). This can be useful to keep the

code clean and store component-specific CSS styles more easily.

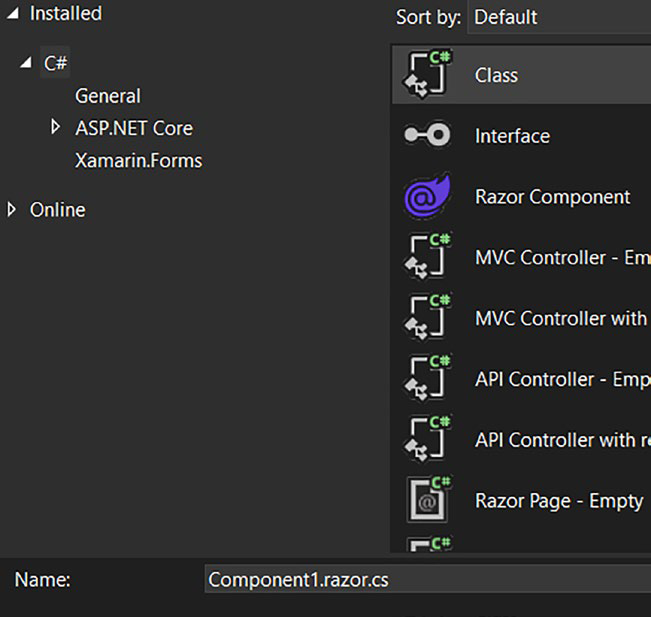

To create a CSS code-behind file, you only need to create a CSS file

where your component (or page) is. The file must be named in a specific

way (as shown in the example for Component1.razor shown in Figure 5-2

and Listing 5-5).

Listing 5-5. YourComponentName].razor.css

<link href="codebehindfiles.styles.css" rel="stylesheet">

To make this work, you will also need to add a specific stylesheet

Listing 5-6 reference in your _Host.cshtml or index.html file (on the client

side). For this, you can use the following format:

[YourProjectName].styles.css

Listing 5-6. CSS Code for Example

.buttonclass {

width:100px;

background-color:blue;

color: white;

}

The example in Listing 5-7 shows a basic style for button.

Listing 5-7. Buttons with CSS Classes

<p><button class="buttonclass" @onclick="@SetText" >Add text

</button></p>

<p class="buttonclass">@texttodisplay</p>

The example component contains a button to which the style is

applied, and remember, the style can be applied only to elements of this

component, as shown in Listing 5-7.

If you try running this example (Listing 5-8), you will see that only the

button in the component has the style applied.

Listing 5-8. Index.razor Page with Example Component

@page "/"

<p><button class="buttonclass">Index button</button></p>

<Component1></Component1>

Creating a code-behind C# file is similar, but it will require some

additional work. First, you need to create a C# file (.cs) based on the

format shown in Figure 5-3.

Figure 5-3. CSS file creation in Visual Studio

Here is the format:

[YourComponentName].razor.cs

The file is shown in Listing 5-9.

Listing 5-9. [YourComponentName].razor.cs

public class Component1Logic : ComponentBase

{

public string texttodisplay;

public async Task SetText()

{

texttodisplay = "test";

}

}

In the file, you will need to change the class name (without renaming

the file itself) and then add inheritance for the Component base. The

example simply has one method that sets the value to a string, which is

displayed in the previously shown UI code (Component1.razor).

Finally, in the component itself you need to declare inheritance

(Listing 5-10) for the previously created class. If you miss this step, it will

not work.

Listing 5-10. Inheritance for C# Code-Behind

@inherits Component1Logic

Local Storage

Local storage in browsers can be used to store user-specific data that is

carried between sessions. Blazor offers a couple of ways to access local

storage, and both have their own upsides and downsides.

The first way is to use ProtectedLocalStorage (Listing 5-11), which is

available only for the Blazor server version.

Listing 5-11. ProtectedLocalStorage Example

@using Microsoft.AspNetCore.Components.Server.

ProtectedBrowserStorage

@inject ProtectedLocalStorage storage

You will first need to do an injection for ProtectedLocalStorage,

and for that you will need the using statement shown in the example

Listing 5-12.

Listing 5-12. Example UI Code

<p><input @bind="examplevalue" /></p>

<p><button @onclick="@(async () => { await storage.SetAsync

("ExampleValue",examplevalue); })" >Set</button></p>

<p><button @onclick="@(async () => { examplevalue =

(await storage.GetAsync<string>("ExampleValue")).Value; })"

>Get</button></p>

<p>@examplevalue</p>

@code {

string examplevalue;

}

The example (Listing 5-12) here is quite straightforward; it will insert a

value, and once you reload the page, you will be able to fetch that value. To

add to new value, you will use SetAsync. This takes the key of the value and

value itself, a basic key-value pair. Then to retrieve the value, use GetAsync

and provide a matching key for your value. This feature allows you to add

any type you want: numbers, strings, or your own custom objects.

If you look at the developer tools and check the local storage

(Figure 5-4), you will notice that the value is encrypted. This is something

to remember if you later want to access your value without using the

ProtectedStorage option.

Figure 5-4. View of developer tools in browser

If you are working with the Blazor client-side version (WebAssembly),

you will have to interact with JavaScript and connect to the LocalStorage

feature directly Listing 5-13.

Listing 5-13. JavaScript Injection Example

@inject IJSRuntime js

For this you will first need to inject IJSRuntime.

<p><input @bind="examplevalue" /></p>

<p><button @onclick="@(async () => { await js.

InvokeVoidAsync("localStorage.setItem","ExampleValue",example

value); })" >Set</button></p>

<p><button @onclick="@(async () => { examplevalue = await js.

InvokeAsync<string>("localStorage.getItem","ExampleValue"); })"

>Get</button></p>

<p>@examplevalue</p>

@code {

string examplevalue;

}

To access local storage, you do not need to write additional JavaScript.

To add a new key-value pair, you can simply access the setItem function,

as shown in Listing 5-13. This will take the key as the first parameter and

your value as the second.

To retrieve your item, you can use getItem, which will only require you

to pass the key of the key-value pair. You will also need to declare the type

of the value you retrieve. However, this will work only for basic types like

double, string, and others. If you need to store something more complex,

you can turn it into JSON and deserialize it after retrieving the JSON string.

Pick and Save Files

Blazor provides a way to directly pick files without having to interact with

JavaScript, but for downloading (saving a file) Listing 5-14 that will not be

the case.

Listing 5-14. Blazor Code for File Picker

<p>

<button onclick="document.getElementById('flpicker').

click()">Pick</button>

<InputFile id="flpicker" OnChange="@(async (args) => await

OnInputFileChange(args))" hidden multiple ></InputFile>

<p>@filesize</p>

<p>@filename</p>

</p>

To pick a file, you will need to use the default Blazor component

InputFile. Styling it can be tricky; therefore, you always want to hide it and

use a button for invoking the file picker instead. To do that, you will need

to give the InputFile and ID and then in the button use simple JavaScript

to invoke the click event Listing 5-15. Notice that we are not using Blazor

to interact with JavaScript; it is done directly in the button and by using

onclick rather than Blazor’s @onclick. With that, you will also want to add

a hidden attribute (to hide the InputFile) and multiple (if you allow users

to pick multiple files).

Listing 5-15. File Picker Initialization Example

@code {

long filesize;

string filename;

private async Task OnInputFileChange(InputFileChange

EventArgs e)

{

foreach (var File in e.GetMultipleFiles(e.FileCount))

{

filesize = File.Size;

filename = File.Name;

Stream str = File.OpenReadStream(1000000,

CancellationToken.None);

}

}

}

If you have multiple files picked, you can use GetMultipleFiles to

retrieve references to them. This will also work for a single file. For each

file you will get some data name, size, and more. To read the file and use

it, you will need to use OpenReadStream and make sure to set your custom

maximum file size as the default is only around 500KB.

To download a file, several options exist, although it will have to be a

custom solution. This particular example Listing 5-16 will show you one of

the ways to deal with it for the Blazor client-side version.

Listing 5-16. JavaScript Code for Downloading a File in the Browser

function downloadfile(name, bt64) {

var downloadlink = document.createElement('a');

downloadlink.download = name;

downloadlink.href = "data:application/octet-stream;

base64," + bt64;

document.body.appendChild(downloadlink);

downloadlink.click();

document.body.removeChild(downloadlink);

}

For this technique, you will first need to set up a JavaScript function.

This takes your desired file name and a base64 string representing your

file. Then, the function creates an element (not visible anywhere), adds

href for the file download, and clicks it, which initiates the download

Listing 5-17.

Listing 5-17. C#/Blazor Code for Downloading the File in a Browser

@page "/"

@inject IJSRuntime js

<p><button @onclick="@Download">Download</button></p>

@code{

async Task Download()

{

string json = System.Text.Json.JsonSerializer.

Serialize(data);

string base64 = Convert.ToBase64String(System.Text.

Encoding.UTF8.GetBytes(json));

await js.InvokeAsync<object>("downloadfile",

"examplefile_" + DateTime.UtcNow.ToFileTimeUtc().

ToString() + ".json",base64);

}

ExampleData data = new ExampleData()

{

val1 = "value 1",

val2 = "value 2"

};

class ExampleData

{

public string val1 { get; set; }

public string val2 { get; set; }

}

}

Since this is a JSON file, we first generate a JSON string from a C#

object. Then we need to create a base64 string, which can be created

from any object in C#, so this does not have to be JSON file. Finally, for

downloading, we need to initiate the JavaScript function, and it will create

a download.

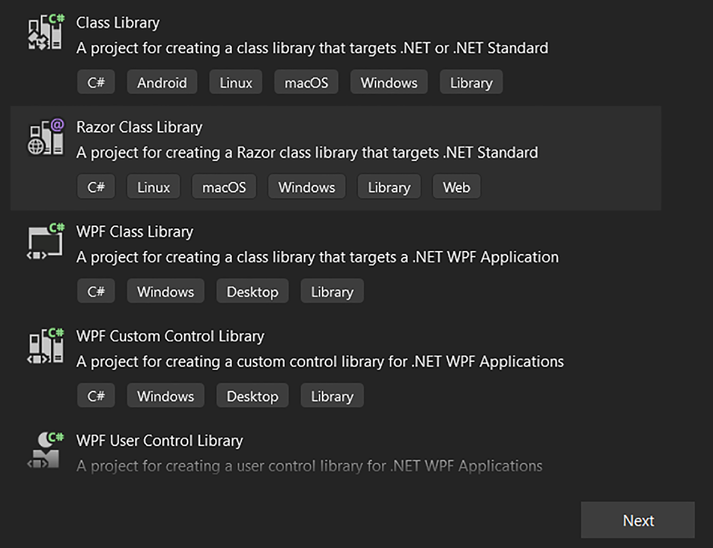

Creating a Blazor Code Library

Just like any C# executable project, Blazor can have class libraries.

These libraries are capable of storing not just classes with logic but also

components and styling. The Blazor library project template is called

Razor Class Library (Figure 5-5) in Visual Studio.

Figure 5-5. Razor class project setup in Visual Studio

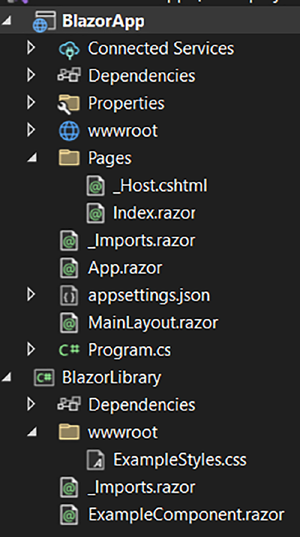

For a basic example, we have one Blazor project and one Blazor code

library project (Figure 5-6). The library contains a new CSS file and a

component, which will be displayed in Index.razor.

Figure 5-6. File contents for example projects

There is only one style here (Listing 5-18) to make a button red

Listing 5-19.

Listing 5-18. CSS Code

.RedButton {

background-color: red;

color:white;

}

Listing 5-19. Button with CSS Class Applied

<p><button class="RedButton">Example component button

</button></p>

The example Listing 5-20 component simply contains a button to

which the style is applied.

Listing 5-20. Example Component Implementation

<p><button class="RedButton">Index page button</button></p>

<BlazorLibrary.ExampleComponent></BlazorLibrary.

ExampleComponent>

Index.razor contains another button, with the same style applied

(from the library).

The result of the code is quite simple (Figure 5-7): two buttons are

displayed. One is from the page itself, and one is from the component that

comes from the library.

Figure 5-7. Output view for the example

There are two important things to do for this to work. The first is to add

a reference Listing 5-21 to the library in your Blazor project, just like you

would add any other code library to a C# project.

Listing 5-21. Reference for CSS File

<link href="_content/BlazorLibrary/ExampleStyles.css"

rel="stylesheet" />

The second thing is to add the reference to the stylesheet file in a very

specific way. This will apply to any JavaScript stored in the library. You

must always use the following format:

"_content/{NameOfYourLibrary}/{LocationOrFileInWWWRoot}"

Background Tasks

Background tasks in Blazor need to be handled with care Listing 5-22, as

any issues related to UI updates can be difficult solve.

Listing 5-22. UI Update from Background Task Example

<p>@fordisplay</p>

@code {

int fordisplay;

protected override Task OnInitializedAsync()

{

_ = BackgroundTask();

return base.OnInitializedAsync();

}

async Task BackgroundTask()

{

var rnd = new Random();

while (true)

{

await Task.Delay(2000);

fordisplay = rnd.Next(1, 1000);

StateHasChanged();

}

}

}

The example here simply runs a loop and every two seconds (2000ms)

sets a new random value. The method BackgroundTask is started in

OnInitializedAsync, without await, meaning that it will start running and will

move to something else. This also means it will be running in a background.

For this to update the UI, you must use the StateHasChanged method.

This should be used whenever a value in the UI needs to be updated.

Countdown Timer Example

This example will show several features from this and previous chapters

joined together in one project.

First, in the code section, we need two variables (Listing 5-23).

TimeSpan will be holding the time, and the system will be subtracting from

it every second. The Status integer is simply the status for the timer. It

is important to note that if you have a bigger project where such statuses

would be reused, it might be worth your time to have an enum set up.

Listing 5-23. Variables for Timer

TimeSpan timeleft;

// 1- running, 2 - paused, 3 - stopped

int status = 3;

For the running state (Listing 5-24), we simply have a button, which

when clicked will change the status variable, which in turn will change

what the user sees. You will later see how the pausing of a timer is done.

Once the timer is paused, the user can see a resume button, which, again,

simply changes the value in the status variable.

Listing 5-24. Timer Setup and Display UI

@if (status == 1 || status == 2)

{

@if (status == 1)

{

<p><button @onclick="@(() => { status = 2; })">Pause

</button></p>

}

@if (status == 2)

{

<p><button @onclick="@(() => { status = 1; })">Resume

</button></p>

}

<p><button @onclick="@(() => { status = 3; timeleft = new

TimeSpan(0, 0, 0); })">Stop</button></p>

<p>Time left: @timeleft</p>

}

Both paused and running views allow users to see the timer display

(time left) and a stop button. When the stop button is clicked, the status

variable is changed, and with that the TimeSpan variable is reset to zero.

The stopped status view (Listing 5-25) is where the user can start the

countdown and set the time in seconds.

Listing 5-25. Timer Setup UI

@if (status == 3)

{

<p>Seconds: <input value="@timeleft.Seconds" type="number"

@oninput="@((args) => { timeleft = new TimeSpan(0,0,Convert.

ToInt32(args.Value)); })" /></p>

<p><button @onclick="@( async () => { status = 1;

RunTimer(); })">Start</button></p>

}

Since we have TimeSpan for storing time, we cannot directly bind it to

the input. Instead, we need to use the oninput event and get the seconds

from that event argument. To complete the two-way binding, we just need

to assign value that we set in the event.

Finally, the start button will change its status to running and execute

the RunTimer method (Listing 5-26) without await; it will run in the

background.

Listing 5-26. Method for Updating the Timer Every Second

async Task RunTimer()

{

while (status == 1 || status == 2)

{

await Task.Delay(1000);

if (status == 1)

{

timeleft = timeleft.Subtract(new TimeSpan(0, 0, 1));

StateHasChanged();

if (timeleft == new TimeSpan(0, 0, 0))

{

status = 3;

StateHasChanged();

break;

}

}

}

}

The method used in Listing 5-26 contains a loop that will run as long

as the status is either running or paused. But, it will only update the value

and display it in the UI if the status is running. Every second it will subtract

one second from the TimeSpan variable and execute the StateHasChanged

event to update the UI. Finally, once the TimeSpan reaches zero, it will

change the status to stopped (3) and once again execute StateHasChanged

to update the UI.

Error Boundaries

Error boundaries in Blazor can wrap specific parts of UI code, which then

in case of an error would only display an error and break that part of the

code. This can be useful when dealing with interactive lists and other such

more complex arrangements.

In Listing 5-27, we have a class object that is set to null. Then in the

paragraph it is set to display val1, which will throw an exception as the

object is null. Normally, this would break the whole page, but since it

is wrapped in ErrorBoundary, it will display an error only for that part

of code. If you only wrap your code in ErrorBoundary, it will display the

default warning. To add your own, you use ErrorContent and then add

wrapped content in ChildContent.

Listing 5-27. ErrorBoundary in Blazor Code

<ErrorBoundary>

<ChildContent>

<p>@exampleclass.val1</p>

</ChildContent>

<ErrorContent>

<p >Something went wrong</p>

</ErrorContent>

</ErrorBoundary>

<p>Still works</p>

@code {

ExampleClass exampleclass;

class ExampleClass

{

public string val1 { get; set; }

}

}

Summary

In this chapter, you saw lots of features of Blazor and learned that some

things are possible in only one of the Blazor types. Therefore, you should

always be careful when you are planning your applications and choosing

Blazor types.

CHAPTER 6

Practice Tasks

for Server-Side Blazor

Now that you are done with learning, you need to practice. We will start

with two tasks for server-side Blazor and explore its use case further.

In this chapter, you will be able to practice the following:

• Setting up a Blazor server project

• Using UI bindings for Blazor

• Executing methods in Blazor

• Handling dependency injections in the Blazor server

Task 1

The first task will be a simple project that merely takes the data from the

user interface, inserts it into a database, and then retrieves and displays

the data. The server-side version is really useful in this case when you work

with simple forms and you need quick access to the server.

Description

Create a product management dashboard.

The user should be able to do the following:

• Insert a product

• Retrieve product list

• Delete a product

This is the product data:

• ID

• Title

• Seller’s name

• Description

• Value

The product list items should also contain a button or other element,

which when clicked will delete the element.

For this project, you will not need to interact with a real database;

instead, a static list will be used. You can find it in the resources.

Resources

Since we are not learning about databases here, we need to create a fake

one. This way, you can focus on Blazor-related matters only.

Create a .cs file according to the code provided (Listing 6-1). This

will be your database, where you will insert your product objects, retrieve

them, and delete them.

using System.Collections.Generic;

namespace BlazorApp1

{

public class FakeDatabase

{

public static List<your product model> products = new

List<DataModels.ProductModel>();

}

}

You can start this project with the nonempty Blazor server-side

template.

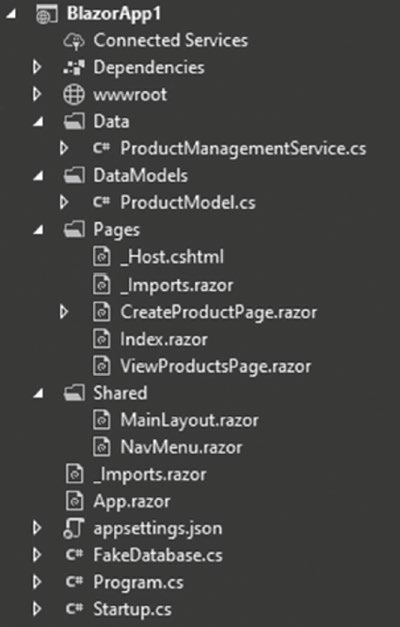

Solution

As usual, there are many solutions to this task, but we will still take a look

at one possibility and explore it as much as possible. We will start with the

general setup of the project and then move to services and then to pages.

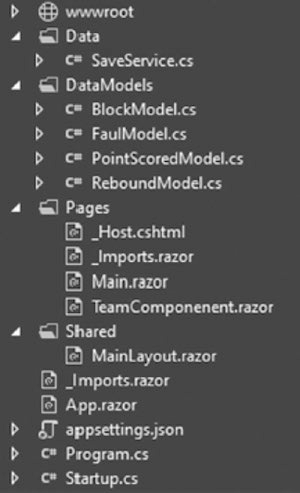

As you can see (Figure 6-1), the project (Blazor server app) has most of

the default contents removed, but we still leave Index.razor, MainLayout.

razor, and NavMenu.razor.

Figure 6-1. The solution project

First, the Shared folder (Figure 6-1) contains our main layout, as well as

the nav menu where we will have the navigation options to our two pages.

We also have the index page, which will contain our navigation links. In

addition, we will created a couple of pages for creating new products and

retrieving the list. For the logic part, we have the Data and DataModels

folders. In DataModels, we will have the model for the product, and Data

will contain our logic. This is a good way to lay out your project so you

know exactly where to put files.